Project Overview

For a course called CS 3210, Design of Operating Systems, I implemented a user-space login system in C language that boots into a login prompt, verifies their credentials using salted SHA-256 password hashes, and then drops privileges with setuid(uid) before launching a shell.

The design mirrors the classic Unix credential storage: a public user database for name-to-UID mapping, along with a restricted shadow-style file that stores password hashes and salts for each user.

Design Doc (Full)

## Security Mechanisms

### Randomness and Salts

The login code uses an AES‑CTR based DRBG to generate salts for passwords. The DRBG keeps:

- a 256‑bit AES key

- a 128‑bit counter

- a small 16‑byte output buffer

On the first use, it initializes its internal state using:

- the current `uptime()` value

- the address of a local variable on the stack

Those bytes are run through `sha256` to produce a uniform initial key; the first 32 bytes become the AES‑256 key and the counter starts at zero. Each call to the DRBG encrypts the current counter value with AES‑256, returns those bytes, and then increments the counter. `generate_salt` simply pulls 16 random bytes from this DRBG and maps them into an alphanumeric alphabet to form the salt string.

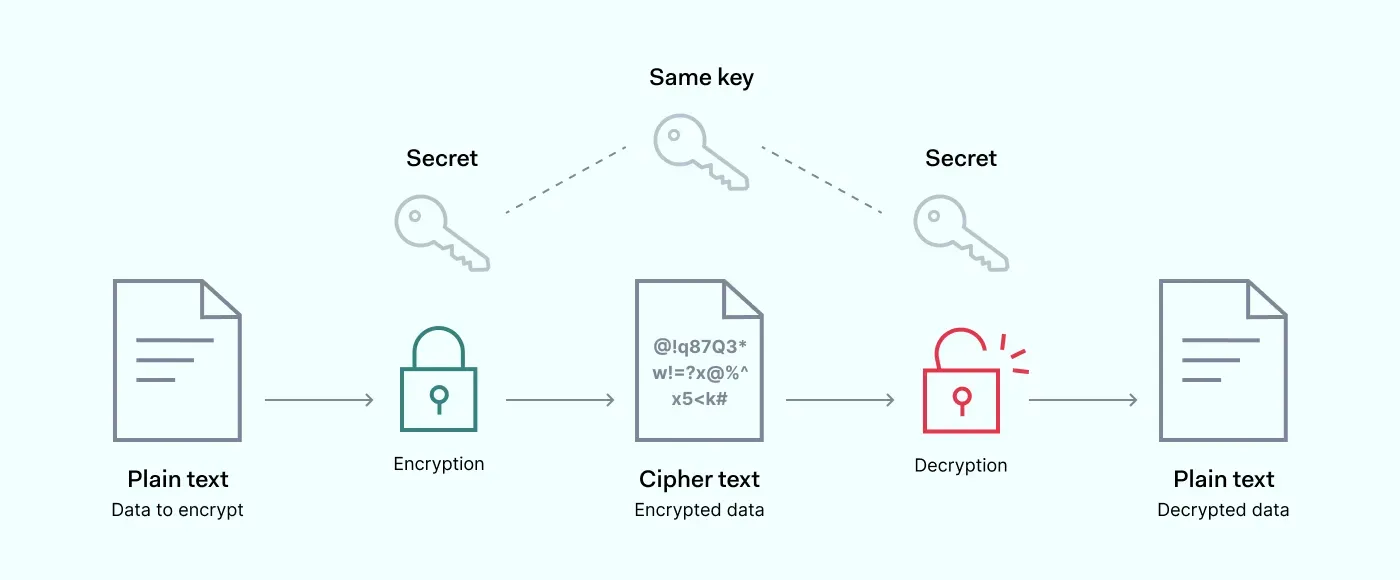

### Password Storage

Passwords are never stored in clear (this would be bad). For each user we store:

- a per‑user random salt

- `sha256(password || salt)`, hex‑encoded

The hashing pipeline in `compute_hash` is:

1. Concatenate the raw password bytes and the salt string into a temporary buffer.

2. Compute `sha256` over that combined buffer.

3. Convert the 32‑byte hash into a 64‑character lowercase hex string.

When a user logs in, we read the stored salt and hash, recompute `sha256(password || salt)`, hex‑encode it again, and compare strings. We never compare plaintext passwords and we never reuse salts across accounts.

### Separation of Concerns: users vs shadow

The design follows the classic Unix split between a public “users” database and a restricted “shadow” file:

- `/etc/users` only contains `username:uid`. This is enough for mapping names to numeric IDs and for picking the next free uid, but it does not expose any password‑related data.

- `/etc/shadow` contains `username:salt:hash`. This file is owned by root and is not readable or writeable by other users.

By keeping salted hashes in a separate file with stricter permissions, we reduce the blast radius if some user gains the ability to read the user list.

### Permissions and Ownership

The login code uses the `chown` and `chmod` syscalls from Part 2 to lock down the credential files at boot. In `init_hook` we:

1. Ensure the directory `/etc` and the files `/etc/users` and `/etc/shadow` exist.

2. Call `secure_credential_store`, which does:

- `chown(LOGIN_DIR, ROOT_UID)` and `chmod(LOGIN_DIR, 0)` so that only root can access the directory.

- `chown(USERS_FILE, ROOT_UID)` and `chmod(USERS_FILE, PROT_R)` so only root (uid 0) can read and modify the user list; other users only get access via the login program’s logic.

- `chown(SHADOW_FILE, ROOT_UID)` and `chmod(SHADOW_FILE, 0)` to make the shadow file completely inaccessible to non‑root.

Because the login binary starts as uid 0 (via `init`), it can manage these files and then drop privileges before running the user’s shell.

### Root Provisioning and Privilege Drop

On every boot, `init_hook` calls `ensure_root_user` which:

- checks `/etc/users` for a `root` entry with uid 0

- checks `/etc/shadow` for a matching `root` credential line

- if either side is missing, it:

- generates a new random salt

- computes the salted hash of the default password `"admin"`

- writes/repairs `/etc/users` and `/etc/shadow` accordingly

This guarantees that a `root` user with uid 0 and password `admin` always exists and that its credentials are consistent.

When a normal user logs in, `login_user`:

1. Confirms that the username is syntactically valid.

2. Looks up the uid in `/etc/users`.

3. Looks up the salt and stored hash in `/etc/shadow`.

4. Recomputes the salted hash of the provided password and compares it to the stored hash.

5. If the hashes match, calls `setuid(uid)` to drop privileges from root to that user.

6. Finally, `exec("sh", argv)` to start the shell under the correct uid.

At this point all user commands run with the user’s uid and are subject to the file permission rules from Part 2.

```

Couldn’t render the Markdown inline. You can still open it here: login_design.md